Bambi got out of the Pan and into the Fire Pan

- David Sifuentes

- Aug 28, 2025

- 13 min read

It’s opening day pretty soon for a new hunting season and across the country deer season and muzzleloader season are on many people’s minds. Modern muzzleloading season is crafted around nostalgia, and could sometimes be considered chivalric, or at least in states with a defined and well established Primitive Season. Kenobi would probably say Kaintuck rifles were elegant weapons of a more civilized age. It should be a season with a much harder setting than general season, and the idea of an unfair advantage of inline space age front stuffers with ballistics marketed comparable to some smokeless calibers seems to miss the point of the season and the hardship endured in the past while trying to put food on the table… or does it?

There’s two schools of thought that are most prominent among muzzleloader hunters. One says whatever “legal” method is getting employed to get venison into the freezer and the other seems to have just as unhealthy an obsession for the other end of the spectrum. “We hunt under these harder conditions because our forefathers did.” At face value this is a true statement but a nuance that it lacks is the common modes of hunting in the 18th and 19th century. The contemporary art of the mountain man and long hunter doesn’t help when it undertones lead you think broski just scored out on his drawn Colorado elk tag and is about to head back to the cabin with one of those fancy Euro mounts.

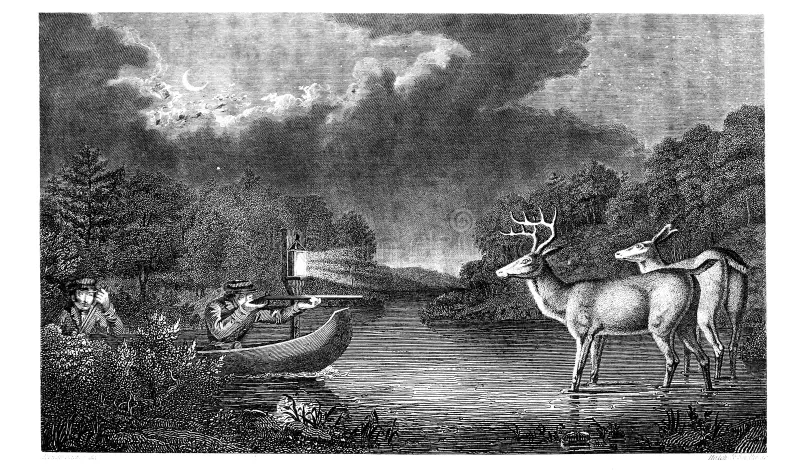

If a Boone and Crockett member actually employed common hunting and harvesting methods of Dan’l, Davy, and their contemporaries, he’d probably be headed for jail and fines. Ultimately we need to face the facts that the decimation of our wild fauna was during the flintlock and percussion period. It wasn’t a problem of an urban mindset either when you consider it was the Indian and the Anglo/French trapper that were responsible for wiping out fur bearers and moving on to a new river to repeat the sad cycle. Popping roosting turkeys? Check. Shooting water bound deer from a canoe? Check. No bag limits? Check. Taking only the choice parts and leaving the rest? Check. Chasing with hounds? Check. Torching for deer? Check.

This soapbox setup has built up to the last part and it was a well practiced part of historical hunting and about as ethical to the modern hunter as dynamiting fish. Fire hunting had long been established before the first American colonists made their way to Texas. We’ll skip most of the early Eastern quotes and segue into Colonial Texas and the Republic.

I will now, for the benefit of sportsmen in the Highlands of Scotland, instruct them how to approach the red deer within thirty yards. The red deer are so very wild and shy, that, I am told, it is most difficult to get within shot of them. This difficulty I will completely do away. My plan is no-thing, more or less, than what, in both North and South Carolina, is so well known, and called FIRE-HUNTING RY NIGHT. I feel a very considerable degree of pleasure in reflecting, that I shall be the means of procuring much diversion and satisfaction to Highland sportsmen, by teaching them, whenever they choose it, how to approach, within a short distance, the wildest and shyest red deer. I will describe the whole particulars. I was an eye-witness to this amusement, when I first went about thirty miles up the country, just after the siege of Charlestown, with my old, intimate, and worthy friend, Colonel Simcoe, then commanding the Queen's Rangers, afterwards General Simeoe, now dead and lost to his country—I say, lost to his country, for he undoubtedly was one of the very best officers in our service. Two American Back-woodsmen went with me; all three of us on horseback: they go on horseback, for fear, lest, creeping along by the edge of the swamps, they might tread on a rattle-snake, of which there are plenty near to the swamps. The rattle-snake, when he hears the stamp of a horse's foot, flies away; for divine nature has so ordained it, that this deadly animal avoids you as much as you wish to avoid it; and no person is bitten by a rattle-snake, excepting he come on it when it lies, coiled up, asleep, and basking in the sun. The Back-woodsman takes a large fry-ing-pan, with a very long iron handle to it; puts about half a dozen middling-sized pieces into it, of the pine-tree, (the knots of the pine,) which are full of turpentine: these, when lighted in the frying-pan, give a very strong and great light. The pine-treeknots were stuck into an iron stanchion, on their tables, in their houses, to light the house by night; for they had at that time no candles, and they give a very great light. He, after lighting this wood in the frying-pan, puts the pan over his left shoul-der, and carries the light behind his head: he then mounts his horse; first putting strong, thick sacks over the rump of the horse, to prevent any fire falling down and burning the animal; and takes a soldier's musket, loaded with buck-shot, in his right hand. The other man follows, about seventy or one hundred yards behind, with a bag of turpentine knots, to replenish the fire in the frying-pan when necessary. I went on horseback, close behind the man with the gun. In following, you must be very particular. The frying-pan must be held directly straight over your left shoul-der, never turning the handle one inch, even to the right or left. When you look before you, you must not move your head, but turn your whole body on the saddle to the right and left, holding the frying-pan firm and straight, by fixing your elbow firm to your body. So far off even as two hundred yards you will see the deers' eyes appearing just like two balls of fire. Remember, for cer-tain, that you go directly up the wind, else the deer will smell you, and you never wil get near to one. The deer, astonished and surprised at so strange a sight, stands stock-still, terrified, and gazing at this very bright light, and permits you to approach him very near. We had not been long out, walking our horses very gently, by the side of swamp, where the deer at night feed; but we found one. Before we came within one hundred yards of him, he ran away. To the best of my recollection, one of ou horses snorted. We had not gone a quar ter of a mile further, ere we found another the Back-woodsman did not go directly up to him, but took his way about thirty yard: on one side of the deer. The animal, I am certain, let him come within less than forty yards of him: he then pulled up his horse, which was going only at a very slow walk. laid his arm over the handle of the frying-pan, supported his musket with his left hand, fired, and shot the deer. The deer was standing rather sideways to him, with his head turned round to the light; so that he shot him in the fore-quarters, just behind the fore-elbow.: The animal did not run five yards. We threw him over his horse, and returned home. There was, when I was in the Carolinas, a positive act of the assembly, imposing a fine on any person who should fire-hunt by night; for some persons, not approaching near enough to distinguish plainly that it was a deer, and no other animal, have shot: young colts, oxen, and heifers; for the eyes of these young animals, at night, by this light, will appear just the same as the eyes of the deer: therefore you must be careful, and see distinctly what animal it is, or you may shoot young cattle.

Colonel George Hanger, to all sportsmen, and particularly to farmers, and gamekeepers; 1814

Now onto Texas

Large game is sometimes hunted in the night, in a manner common in the south western states, by what is called "shining," or "shining the eyes." The huntsman carries a lighted on his head, or sometimes a quantity of burning combustibles in a frying pan bebind him, resting the handle on his shoulder, and has his rifle ready in his hand. Animals are attracted by a bright fire in the dark, and their eyes reflect the light so strongly, that they are perceptible, like sparks or coals, from a considerable distance. The position of the light prevents the huntsman from being distinctly seen, though at the same time it does not dazzle his own sight; and while the deer, bear, or other game stands gazing with wonder, he has an opportunity to take deliberate aim. This practice however is not unattended with danger: as it is impossible under such circum-stances, to discriminate with certainty between the eyes of wild beasts and those of domestic animals; and in some parts of our own country, as in Kentucky for instance, wherever there are many settlements, hunting in this manner is forbidden by law. A ludicrous hunting party on this plan was called out on the Prairie one night about the time of my visit at Anahuac. Some of the sportsmen in the huts and barracks were waked by the cries of the dogs, which had evidently brought some animal to a stand near by. They yelled so merrily, that numbers were soon out with their rifles and fowling pieces, half dressed, and scampering off to the spot. There they found the dogs barking up a tree, where the shade was deep, and where they looked long before they could perceive any thing. At length, by lighting a ra they discovered a pair of eyes shi-ning far above them; and their pieces were immediately raised, supposing they had treed a rackoon. Colonel Bradburn, however, who was among the foremost of the hunters, suddenly ordered all to lower their guns; and sending up one of his Mexican soldiers, recovered a favorite kitten, which had strayed from his quarters, and having been pursued by the dogs, had caused this muster, and incurred so narrow a risk of its own life.

A Visit to Texas

In the night they are decoyed by fire and killed. A hunter fixes a blazing Torch in his hat, or has another person to carry one just before him; the deer will stand gazing at the light while he ap-proaches, and by the brilliancy of their eyes and space between them, calculates his distance and takes his deadly aim. He must take especial care, however, that the shadow of a tree or of any thing else does not fall upon the deer; for in that event, he starts and is off in a moment.

A Trip to the West and Texas

I left on the 4th of October and arrived two days later at B's farm hunt for deer was being planned, and I joined eagerly since I had never participated in one of these. Toward evening we went into the forest; behind us was a Negro with a flaming pan of coals which was fastened to a long handle and carried backwards. As soon as the deer see the fire they stand very still, and their eyes, which are two gleaming dots in the darkness, make a perfect target. We had hardly pressed forward half an hour when I became aware of such an indication of a deer. Quietly I took careful aim and made a fine hit. It did not give me any real pleasure to be the hero of the day. The same evening the Negro brought in the booty, and soon the tempting odor of meat roasting on the spit pervaded the house.

Sketches of life in the United States of North America and Texas

We had left Houston rather late in the day and got benighted. We saw a light in the distance apparently in our track. We approached it, and crack went a rifle ball. We sang out lustily that although we were dear, we were not quite the sort of game to be taken in that way. I need hardly say that the light we took for a house was a pan of pine sticks, burning by some deer hunters. In a word they had"shined" our horses' eyes, taking them to be those of deer They apologized to us and we pursued our way.

On the Different Sorts of Hunting and Species of Came in Teas Deer—1st: (Deer have been met with with 36 points on antlers or 18 on each side. Deer shed their horns, and every year a new point comes out). By merely shooting them down in day light with the rifle; this is deer-stalking and hunters generally get up to the game from 8o to 100 yards-others fire when they can discover plainly the eye of the animal. When game is scarce, then dogs are employed to scent them. Deer, if not badly wounded, will run and dodge about, then dogs are useful to catch them, particularly in the woods. 2nd: By fire hunting. This is performed by one person carrying an iron pan basket filled with burning pitch-pine with which they shine the eyes of the deer, and thus are enabled to shoot the deer in the darkest nights.

Wednesday, November 29th, 1843: 8 A.M. 50°. Rainy and breezes from N.W. The sudden change of temperature gave me a touch of chill today. In 1841 provisions were scarce in Texas and consequently high in price; then it was that the settlers carried on the "fire hunting" to a great extent. A party of three or four would in a day or so shoot down some 20 to 30 deer. The best way to go "fire hunting" is that the hunter be assisted by a Negro to carry the fire or pine wood. The hunter being on foot or horseback, carries the fire pan full of lighted pine wood over his left shoulder, left handed people the reverse, proceeding cautiously through the woods. Should there be any deer about they tiously through the woods. Should there be any deer about they look towards the pan of fire, and in a moment the hunter sees a reflection of the light in the eyes of the deer. This is called "shin-ing the eyes" and this in the line of his shadow, which shadow is elongated by a depression of the pan, and vice versa. Deer's eyes may be shined at a 100 yards or more, then they look like a horizontal streak of dim light, but on nearing the deer both eyes will be seen distinctly of a bright light bluish colour. Horses, cats, or human eye did not succeed with us. The hunter generally approaches to within 40 or 50 yards of the game, so managing his pan of fire that he preserves "the shining" on the eye or eyes; he then draws the long wooden handle of the pan forward and makes it a rest for his rifle; aim being taken, the animal seldom escapes. A good hunter can shine a deer's eye 100 yards. In this same manner other quadruped may be taken, even a hawk's eye may be "shined."

Arrival in Texas in 1842, and Cruise of the Lafitte, by a Traveller

There are several modes of Western deer-hunting, and all equally primitive. Sometimes the hunters resort to a favourite haunt of the game, such as the neighbourhood of a "salt-lick;" and while a part beat up their retreat with the dogs, others remain in ambush near their usual crossing-places at the streams and swamps, and shoot the deer as they pass. In the night they are decoyed and killed by a mode familiar to the Western hunters, and called "shining the eyes." A hunter fixes a blazing torch in his hat, or employs a person to carry one immediately in his front. The deer stands gazing at the light, and the hunter calculates his distance and takes his aim, guided by the brilliancy of the animal's eyes and the space between them, being especially careful that the shadow of a tree or any other object does not fall upon the game. Experienced woodsmen say that, in the season when the pastures are green, the deer invariably quits its lair at the rising of the moon. Keeping this hour in view, the hunter rides through the forest, with his rifle on his shoulder the recting a keen glance towards the adjacent shades. moment the deer is in sight, he slides from his horse, advances under cover of the largest trees, until he gets within rifle range, when he fires, and rarely fails in bringing down the quarry. In the cloudless nights of summer, when the moon is abroad in the splendour of the southern latitudes, it is a most exhilarating pastime to lie in ambush near the resort of the deer, ensconced behind an artificial screen of green boughs, or perched among the thick branches of a spreading tree.

Texas; the rise, progress, and prospects of the Republic of Texas

Deer were very numerous, and I have seen as many as 200 playing and sunning themselves in one bunch, where they had gathered from the Sulphurs, Bois d’Arc and Sanders Creek in the spring, lazily eating the abundant grass and cavorting and playing and enjoying themselves. Well do I remember the sport we had in racing, chasing and catching deer with greyhounds in those days. How we would test the speed of our horses and the endurance of our dogs in the hunt and race for deer. We did not kill for lust’s sake, but for sport’s sake. It was easy to kill any number with our guns, but we tried our skill in choosing the biggest, and had contests to see who could kill at the greatest distance and with the cleanest shot. The deer in those days were so numerous that they would do great damage to our roasting ears and pea patches’, and we would flash them with our fire pans, their eyes shining like stars.

The way Uncle Joe got rid of the coons and the droll and interesting manner he explained it are reminiscences I cannot help but think are novel. He made a fire pan light to shine the coons’ eyes by tying a frying pan handle to a pole and setting fire to rich pine knots, put them in the pan and flash them in the eyes of the coon, then blaze away with his flint-lock shotgun, and the coons would drop in multitudes, while those that could would scatter helter skelter in every direction in their haste to get away.. His bear and coon dogs followed up the chase until they found a big hollow tree, about forty feet high, that had been broken by a big storm. The tree was about four feet wide, and into this hollow the coons tried to hide, their tails, in a conspicuous heap, hanging out at the opening near the ground. Here a battle royal ensued until the bear and coon dogs had dispatched the pest, and their hides were hastily taken and loaded later for the market with bear, buffalo, panther, deer and wolf skins, and set on pack ponies to be taken to Sam Fulton’s store, on White River, Arkansas, a distance of about eightyfive miles

Early pioneer days in Texas

These accounts certainly draw a different picture than what many people imagine of the frontier and the means by which it was eventually subdued. And the lack of fear concerning what was being shot at on the other end virtually created an early game law in some places, but less for the sake of deer and more for preserving livestock. We’ll explore other aspects of the 19th century hunting experience another day but just remember for the next time someone sends a round ball whistling past you that you must loudly remind them that you are DEAR not DEER!

Comments