“Wild and Wonderful” Appearances

- David Sifuentes

- Aug 24, 2025

- 24 min read

Back in 2021, I posted what would become the most popular post for the blog to date so far. In it we went through a very basic summary of the clothing styles of Northern Mexico. Some things stayed true, some things I’ve learned about along the way and was pretty wrong about and it’s time we revisited the topic in depth. We’ll do a break down in this post of all the accounts known to me describing Tejano clothing broken up by town and year (1820-1860), and even breakdown an osmosis of items into Anglo culture. An amazing array of diversity will begin to show itself even within a small region. In a future post we can focus on what items are best for historical interpretation and the nuances that cam be applied. I’ll sign off here and let y’all enjoy the following passages.

East Texas- 1820-1860

some Mexican and some American, strangely dressed, more or less in the style of the Indians, always wearing at their narrow deerskin belts the long pointed knives that serve a thousand uses. When we passed near them they interrupted their trek, and, leaning over the horns of these powerful oxen, whips over their shoulders, they exchanged some insignificant words, saluted if they were Spanish, or gladly accepted a swallow of grog if they were descendants of Englishmen. Half-sleeping heads poked out sometimes from between the covers of the wagon. When the retinue had caught its breath, when the impatient horses shook their manes and stamped their feet, then a “good-bye sir” or an “‘adios senor caballero” ended the exchange.

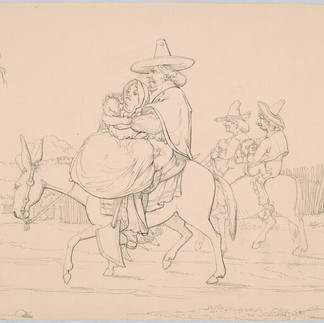

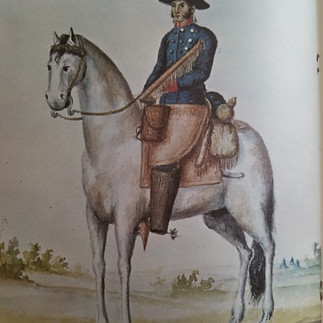

The next day, after two hours of rest, we looked forward to bridling and saddling our mounts, to reach the village of Nacogdoches, the destination of our journey, by the same evening. Already we were hearing Spanish spoken in homes, and instead of English saddles which hardly cover the horse’s back, instead of riding whips and narrow hats, we saw dignified horsemen with large sombreros, their wide brims turned up, pushed back on their heads, red-tasseled horsewhips, and enormous spurs, sonorous and shiny like those of cavaliers of old. In a word, England, imitated by all Americans, was giving way to Spain, in the form of the Republic of Mexico.

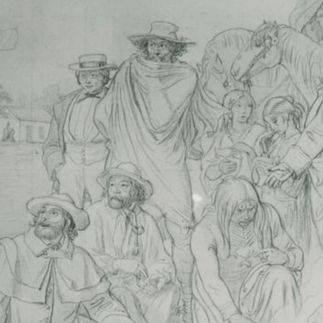

Our first encounter was with a Mexican caravan. Beside a stream rose up a vast parasol of palmetto leaves, and under this canopy was seated a Spanish lady with a Negress. A few steps away, horses and mules were grazing with saddles and supply packs on their backs, and the “‘hirelings,” a type of salaried servants who spend their lives escorting travelers, were resting under a tree—some lying down, others smoking or keeping watch. All had pistols and daggers, while from their buffalo-hide saddlebags were attached long cavalry swords. Their arms, along with their beribboned flat wide-brimmed hats, green jackets and wide belts lent these Mexicans the appropriate character for singing quite naturally “Yo que soy contrabandista,’’>! although by nature, they share with Indians their dark and severe faces, the leather chaps to protect their legs from brambles, and the triangular bearskin scrap strap that hangs down in a triangle and holds the stirrup. This little troop looked so strange, so new to me, so different from the rest of the scenes I had witnessed in America, that I stopped, perhaps impolitely, to contemplate it

One evening we had gone to the main gate of the encampment. The colonel was talking with his aides, handsome horsemen, each leaning on a large, curved sword, wearing a belt of buffalo hide, spurs with a layer of silver on a red background, pants open to the calf and decorated with loops and golden buttons, and the bottom of the legs covered with a piece of well-tanned leather, tastefully stitched.

A horse race was announced for the next day. The Mexican commander arrived in full dress, with aides in dazzling uniforms. Their chaps, covered with pieces of leather artistically embroidered with porcupine needles, enclosed the legs of the horsemen and joined together at the waist, thus protecting the lower body. When the chaps are opened, they hang down to the bend of the horse’s hind legs, and the sun glistens on their elegant decorations, the spurs shining so brilliantly they blind the eye. Feather-trimmed hats, a pair of pistols and an ax complete the equipment of the horseman

Pavie in the borderlands : the journey of Théodore Pavie to Louisiana and Texas, 1829-1830, including portions of his Souvenirs atlantiques

Crossed a watercourse called Bidais (pronounced Beedeyes, and so written by many of the illiterate country people); the rain of yesterday had swollen it very much. Arriving at the cabin of Eduardo Ariola, a Mexican, was informed that it was so full that we should have to swim. Met here Dr. Field, who left Nacogdoches on Saturday, returning, who said he could not cross. But we prevailed on a young Mexican, who called his own name Dolores Ariola, to show us the ford, which he readily undertook. Coming to a creek which had flowed out beyond its banks upwards of 100 yards, he manfully waded in and sounded the bottom to point out to us a safe path. We took our saddle bags on our shoulders and followed him, our Texan fellow traveler, Whitely, first, and I next. It took the poor Mexican up to his arms. He was dressed only in shirt and cotton trousers and shoes, and I got over withonly one foot a little wet… Our young Mexican friend ran on with us in his wet clothes, to show us across that, and on the way very obligingly instructed me in the Spanish vocabulary, as far as there was time to make inquiries.

From Virginia to Texas, 1835. Diary of Col. Wm. F. Gray Giving Details of His Journey to Texas and Return in 1835-36 and Second Journey to Texas in 1837

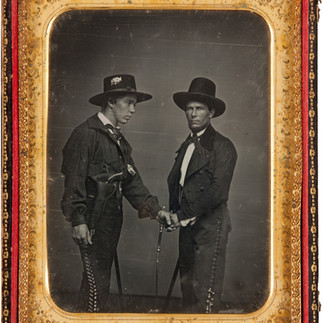

We passed large troupeaux of cattle and cabalgadas of horses and mules on their way to Houston, driven by Mexican arriéros whose odd dress and bearing strikes the stranger with surprise. Mounted on Spanish horses, or well trained mules, with heavy Spanish saddles and bridles, enormous spurs, and large sombreros — hats covered with green oil cloth, with silver bands, and tassels, and buckles, and rich ponchos over their shoulders, their legs protected by mountain goat-skins from the brushwood and the rain, with long whips and waccos, or drinking shells made of gourd, attached to the pommel of their saddles, they have altogether a "wild and wonderful" appearance. The constant crack of the whip, and the oft repeated vamos to the mules and horses, produces a spell-bound and startling effect.

Prairiedom: rambles and scrambles in Texas or New Estrémadura, 1846

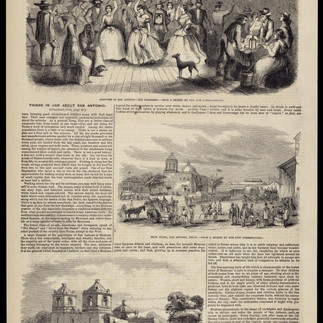

San Antonio 1820-1860

Ciudad de Béxar resembles a large village more than the municipal seat of a department. There is no paved street and no public building. Trade with the Anglo-Americans, and the blending in to some degree of their customs, make the inhabitants of Texas a little different from the Mexicans of the interior, whom those in Texas call foreigners and whom they scarcely like because of the superiority which they recognize in them. In their gatherings, the women prefer to dress in the fashion of Louisiana, and by so doing they participate both in the customs of the neighboring nation and of their own.

Journey to Mexico during the years 1826-to 1834

On the day after the battle, a Mexican belonging to the Texian service who was dressed as an American, was reconnoitering the prisoners and on approaching a number of females who had been taken among the others, one of them throwing herself into the posture of a suppliant addressed him as follows; "Senor God demme(God damn) no me mata por el amor de Dios y por la vida de su madrecita" ! On being answered in her own language she turned to her sister & said, Hermanita! mira! ese senor Godemme habla la lingua cristiana como nosotros !

No 1666, Lamar Papers, volume 3

There was little either in the copper color of the females, who were small and delicate, or their dress, which, in some instances, was of silk but most generally consisted of calico calculated to inspire a high idea of their beauty or taste. The male part of the assembly paraded the room, with large brimmed straw hats that almost concealed the face, dressed in blue roundabouts and pantaloons so wide at bottom as to look grotesque and outlandish.

Texas in 1837

The population of San Antonio may be divided into several as Rancheros, or herdsmen, a rude uncultivated race of beings, who pass the greater part of their lives in the saddle, herding cattle and horses, and in hunting deer, buffalo, or mustangs. Unused to comtort, and regardless alike of ease and danger, they have a hardy, brigand sun-burnt appearance, especially when seen with a slouched hat, leather hunting shirt, leggings and Indian moccasins, armed with a large knife, musket, or rifle, and sometimes pistols. To this class belong the peons or labourers, who in Mexico are little better than slaves. The second is a link between the Mexican Indian and Spaniard, are somewhat civilized, superstitious and have less energy than the Ranchero. They reside in the city and its suburbs, cultivating their beautifully situated labors (177 acres] or farms on either side of the gently running river, appearing to be perfectly inde pendent and contented. Their usual dress is a broad brimmed hat of a reddish colour, or white, the band ornamented with silver ornaments or coloured beads, calico shirt, wide trousers, with a fancy coloured sash or girdle about the waist and the jacket thrown carelessly over the shoulder. Early in the morning they go to mass, work a little on the labores, dine, sleep the siesta, and in the evening amuse themselves with tinkling the guitar to their dulcines, gaming, or dancing.The females of this class are kindly and agreeable; they dress plain and tastefully and know how to develope the elegant proportion of their persons, particularly when tripping to matins, or vespers, their hands and faces coquettishly covered with the black mantilla or silk shawl-these are the votaries of the Fandango for which San Antonio is so justly distinguished. Nightly, while yet fresh and buoyant with the exhilerating effects of the siesta or bath, they flock to the scenes of mirth and music, conducted with decorum and without the restraints of announcements, bows, and introductions.

Arrival in Texas in 1842, and Cruise of the Lafitte

The costumes were very simple, dresses of light colored printed calico, with some ribbons. All were brunettes with complexions more or less fair, but generally they had magnificent black eyes which fascinated me. As for the men, they wore usually short jackets, wide-brimmed hats, and nearly all the Mexicans wore silk scarfs, red or blue or green, around their waists.

Reminiscences of a Castro Colonist Republic of Texas, 1843 - 1844 Auguste Frétellière

The dress of the men is picturesque and graceful, although not so rich as in the interior of Mexico. The broad-leafed hat is decorated with silver ornaments; the vest is short, and, when it is of buck-skin, the sleeves are open to the elbow, and ornamented with silver buttons. The pantaloons, too, are garnished with buttons, and open to the hips, but buttoned from the knee upwards. They are of skin, cloth, or blue velvet, bordered with large bands of black velvet. cincture of blue or red silk, with fringe, completes the costume. The Mexican women are scantily clad, wearing only a chemise with very low front, and a petticoat. When they leave the house, they wear a gown of thin silk, and cover the entire person with a scarf, which hangs about them in the most graceful folds.

Missionary adventures in Texas and Mexico. A personal narrative of six years' sojourn in those regions

The dress of the men is picturesque and graceful, although not so rich as in the interior of Mexico. The broad-leafed hat is decorated with silver ornaments; the vest is short, and, when it is of buck-skin, the sleeves are open to the elbow, and ornamented with silver buttons. The pantaloons, too, are garnished with buttons, and open to the hips, but buttoned from the knee upwards. They are of skin, cloth, or blue velvet, bordered with large bands of black velvet. cincture of blue or red silk, with fringe, completes the costume. The Mexican women are scantily clad, wearing only a chemise with very low front, and a petticoat. When they leave the house, they wear a gown of thin silk, and cover the entire person with a scarf, which hangs about them in the most graceful folds.

Texas; with particular reference to German immigration and the physical appearance of the country; described through personal observation, by Dr. Ferdinand Roemer

I do not know why, even now-but the fact that, contrary to the taste of his nation, he wore a light " foraging-cap," instead of a lumbering hat, made me suspect him more than the watchful glance of his dangerous eye. His other clothing consisted of light goat-skin sapatos, or high shoes, white linen trowsers oper from the knee down, and loosely clasped with small gold buckels, a jacket also of white linen, and a thin but beautiful serape, or Mexican blanket, thrown negligently, but gracefully over his shoulders As I turned he dropped one end of the last, and raised his cap with the easy air of a polished gentleman;

Ciation still needed- 1846

“The Ranchero, or herdsman, has a preponderance of Spanish blood over the Indian.Still, he is an uncultivated being, who passes thegreater part of his life in the saddle, herding cattle and horses, hunting wild cattle, mustangs, deer, and buffalo. Unused to comfort, and regardless of ease and danger, he has a hardy, brigand, sunburnt appenrance, especially when seen with his high, broad-brimmed hat, buckskin dress, Indian pouch and belt ornamented with various-coloured beads, armed with his rifle, pistol, and knife.He is abstemious in the way of food or strong drink, but passionately fond of his " cigarito do oja de maize." As a useful and judicious companion on a long journey, or on a trip into the woods, it would be difficult to recommend his equal. The Peon, or labourer, has generally more of the Indian in his composition than the former. He is superstitious and ignorant, and has but little of the energy of the Ranchero. The Peon resides in the city and suburbs, tilling and cultivating the productive land, or " labores (small farms), and appears of a contented disposition. In Mexico the Peon is nearly as much a slave as the Negro is in the southern states of America. His usual dress is a calico shirt, wide calico trousers, a fancy coloured girdle about his waist, his jacket thrown carelessly over his shoulder in summer, a broad-brimmed hat, the band studded with silver ornaments and coloured beads. Early in the morning he goes to mass, then to work; after dinner he sleeps his siesta; and in the evening amuses himself by tinkling his rude guitar to his mistress, dancing zapateos, smoking, and gambling at times. The females of the Rancheros and peons are pretty, good-natured, and obliging. They dress plainly, but tastefully; and well know how to show off their figures and feet when tripping to matins or vespers, their heads and greater part of their faces coquettishly covered with the black mantilla. These are the votaries of the bayle and fandango: they flock to the scenes of mirth and music, conducted with decorum and gentleness. From early evening to the soft hour of twilight, they may be seen, in the summer season, going in joyous groups to sequestered parts of the river, to bathe; and there the eurious eye might oceasionally observe them gliding about in the limpid stream, their regularly-formed, bronzed faces peeping above the surface of the water, and their black hair floating over their shoulders.

The Sporting review, ed. by 'Craven'.: Volume 20, 1848

The population of San Antonio is divided into three classes. The third is the connecting link between the savages and the Mexicans, and are termed Rancheros, (or herdsmen) a rude, uncultivated, fearless race of men, who spend a great part of their lives on the saddle, herding their cattle and horses, and in hunting deer and buffalo, or pursuing mustangs. with which this country so fully abounds. Unused to comfort, and regardless alike of ease and danger, they have a hardy, brigand, sun-burnt appearance, especially when seen with a broad, slouched hat; a red or striped shirt, deer-skin trowsers, and Indian moccasins. The second are a link between the Mexican and the , or Castiltan, and are somewhat more civilized, more super-stitious, owing to the influence of the priest, and yet possessed of less bravery, less generosity, and far less energy than the former. They reside in the city, with but scanty visible means of support, and without the least effort to procure. the comforts of life; still they vegetate, and appear to be perfectly independent and contented. Their usual dress is a broad-brim white hat, a roundabout, calico shirt and wide trowsers, with a red sash or girdle around the waist. At an early hour of the day they go to mass, then loiter out the morning, sleep through the afternoon, and spend the night in gaming, dissipating and dancing—-but they drink but little liquor.

The mountain sentinel (Ebensburg, Pa.), February 27, 1851

The dress of the men generally, consists of under clothos of white cotton, over which they wear looso jackets of tanged buckskin, and loose trowsers of the same material open at the sides, where they aro looped or buttoned with silver. Both coats and trowsers are often tastefully ornamented with beads of various coloured leathers, wrought into a variety of patterns; niso with tamels, fringes, &c. Round the waist is a silk sash, generally of n crimson or green colour, on the hond the sombress, resembling those hats seen in the pictures of brigands; and on the feet mocasina of buckskin, elegantly wrought with silver or bends. This costume in completed by the Mexicun blanket, made of fine wool, and displaying various colours and patterns. Theso blankets are home manufactured, and of such admirable texturo as to be almost waterproof. The method of wearing tho blanket is to double it in the length, and one end being held in the left hand, and peased over the left shoulder, goes round the body, and being gain held in the right hand, three feet from the other extremity, is again prased over the left shoulder, and goes down on the back. It presents, when thus worn, a very graceful appearance. When on horseback, the head passes through a hole wrought in the centre, from whence it hange down in front and rear, completely protecting man and horse from the inclemency of the weather. The women wear loose cotton garments, like morning dresses, of various colours, without any covering on the head, but having the hair plaited. They are partial to rich ear-rings, and jewellery of all kinds

Recollections of western Texas : descriptive and narrative. Including an Indian campaign, 1852-1855. Interpersed with illustrative anecdotes. / By two of the U.S. mounted rifles

Goliad 1820-1860

Among the poor people, the clothing [of the men] consists of a shirt made of shirting material that is always clean and white. (But many men do not have this.) They wear also a jerkin and trousers made of deerskin, which are slit halfway up the calf, and under those they wear undertrousers of white muslin that show below the trouser legs. They wear shoes or sandals that they make themselves and fasten to their feet with straps. The wealthy wear trousers and a jacket of white linen or of [some other] cloth. I have seen the women of the wealthy class dressed in muslin, cotton, and even in silk clothing; on special occasions they wear also the mantilla. Moreover, they wear better shoes than the men, although one occasionally sees the most elegant women [going about] barefoot. The lower class people wear clothes of inferior fabrics.

How soft have the inhabitants of the cold climate become in comparison to the inhabitants of the warm zone! Would a German woman be able to survive if she had to spend a night in the wind, rain, and freezing temperatures huddled under a bush and clothed only in a muslin dress and wrapped in a rug?

At such social events there does not appear to be a distinct segregation of the classes. Judging from their dress, there were some individuals present from the richest as well as from the poorest classes. Every woman appears to acquire for herself a ball gown for her whole life: The dresses that they were wearing fit them so poorly, I can hardly imagine that they were made for them. The cut of the dresses is very old-fashioned with an extremely short waistline. The women appear to like pretty combs a great deal. There were also many golden chains to be seen there, but they may have been of alloy.

John Charles Beales's Rio Grande Colony : letters by Eduard Ludecus, a German colonist, to friends in Germany in 1833-1834, recounting his journey, trials, and observations in early Texas

Rio Grande Valley 1820-1860

We had not been there very long before we were suddenly surrounded by a large herd of goats. A distinguished and handsome man, about thirty years old, was following them. He was dressed in buckskin and was carrying over his shoulder a calabaza, a cabestro, a frazada, and a sack in which he was carrying corn. He had rested his firearm against a tree. He approached us with a noble demeanor and offered his hand. In good faith I grasped the hand of this son of the prairie and shook it. After a brief conversation, he took his leave with the courtesy typical of Mexicans and walked away like a king into the wide prairie, driving his numerous companions ahead of him.This man has no-other bed than the earth and no other tent than the sky. Winter or summer, it makes no difference to him. If he gets thirsty, then he milks one of his goats, and if he gets hungry, then he slaughters her young kid. Ifhe needs corn, then he goes into a town and trades from his abundance for some. He frightens the Indians by his formidable behavior. So, he has no worries and has the most freedom of any man on earth.

When I reached the riverbank, I saw that the canoe was at the opposite bank and I had to wait. Then a young Mexican girl came out of a hut that was on the high bluff of the river. She was about fifteen years old with a youthful slender build. Her clothes, although clean, indicated that she belonged to the lower class. She had on a fine white shirt that hung far down from her shoulders and a cotton dress that because of the heat was loosely fastened. Neither shoes nor sandals protected her small feet from the burning sand

That is the same maneuver that I use myself to kill snakes, but in view of the danger involved, I have a great advantage in my cowhide boots over Antonio, who was wearing only a few scraps of rawhide tied to his feet with thongs. If the snake has just enough room to turn his head a little, Antonio would get bitten for sure

John Charles Beales's Rio Grande Colony : letters by Eduard Ludecus, a German colonist, to friends in Germany in 1833-1834, recounting his journey, trials, and observations in early Texas

These people appeared to have been above the ordinary class; the man was genteelly dressed, and his wife the same. She appeared to have been making her husband some shirts of very fine linen. She had made two and was at work on the third. There was a large quantity of the same kind of goods found in the house.

Comanche bondage: Dr. John Charles Beales's settlement of La Villa de Dolores on Las Moras Creek in southern Texas of the 1830's / With an annotated reprint of Sarah Ann Horn's narrative of her captivity among the Comanches, her ransom by traders in New Mexico, and return via the Santa Fé Trail

The dress of the men in this city varied much. Some of the more influential and wealthy, with such an example as now they had before them, of well dressed officers and American citizens, copied it as set; and dressed in neatly made and fitting coats, pantaloons and vests, cravats, shoes and boots, with American hats, &c. But those dressed "A la Mexicana," wore short waisted pantaloons, (called calzones,) without suspenders; open on the outside seam of each leg nearly to the waistband, with a row of large gilt or silvered bell buttons down this outside seam, to close, it as far as the taste of the wearer required.—These pantaloons were of cotton, or more generally of dressed buck-skin, with a profusion of ornamental needle work in bows, flowers, &c., &c., conspicuous on the sides and front; beneath this pair, another of white or blue was worn, showing all along on the outside of the leg, where the outer ones were open;— this inner pair were called calzoncillas. A cotton or linen shirt, always clean and nice, with a wide brimmed sugar loafed hat of palm, (called a sombrero), with a cord-like ornamental band around it, (called toquilla), with two silver screws with large flat heads to them, showing on the outsides, passing through the body of the hat;—these are used to fasten, by each end, a strong ribbon, which passes under the chin, to keep the hat on when riding in the wind;—slippers made of thin, half tanned leather, of goat skin, useless when wet, or sometimes sandals,—no socks, gloves, or cravat; —in shirt, hat, pantaloons, and slippers, they considered themselves dressed. —If more was necessary, on account of cold, an horongo, or ornamental blanket, worked in figures, diamonds, circles, squares, &c., in red, white, blue, and green colors, was added. —This had a slit in the centre, through which the Mexican put his head when on horseback, and the whole blanket hung around him in its gaudy colors. At other times, laying it on his neck, he threw the right hand side across his breast and over his left shoulder.—In this array, imagine the Mexican on foot before you,—with sombrero, blanket, double pantaloons, and slippers, and commonly an enormous pair of spurs on his heels, and a little paper cigar in his mouth. —Instead of the horongo, however, the better class wore a finer article of the blanket kind, called a "serape."

The twelve months volunteer; or, Journal of a private, in the Tennessee regiment of cavalry, in the campaign, in Mexico, 1846-7

There is a Mexican yonder, leaning gracefully on the pummel of his saddle ; his dress is that of a better class of citizens, and has a kind of theatrical banditti look, that would have delighted Mr. Crummels amazingly. His hat is a palmetto, of a rakish cut, covered with glazed cloth, and ornamented on the sides of the crown with silver balls, that resemble stop-cocks on the head of a steam boiler. These ornaments have caused a great deal of speculation in our minds, to comprehend the character of mental calibre and education, that conceives them to be useful and ornamental. His linen is of most excellent quality, and wrought with an abundance of needle-work. His pantaloons of dressed leather, ornamented with gay cord and a gross of metal buttons, opened from the hip down displaying most coquetishly, wide white drawers. He is puffed up with the gas of self- esteem, as a hard-blown bladder is with wind, and seriously believes, that he is the most distinguished piece of humanity under the sun.

Our Army on the Rio Grande: Being a Short Account of the Important Events Transpiring from the Time of the Removal of the "army of Occupation" from Corpus Christi, to the Surrender of Matamoros

One man, dressed in a red shirt and blue trowsers, reclined in the shade of a broad-brimmed, stift', black hat, on a blanket, spread upon the ground, smoking a cigarito. His eye turned sleepily towards us as we passed up the bank, but he did not address us. Woodland said he was a Mexican corporal, and was then standing guard over the landing

During the ride we met but one man. This was a Mexican, who was mounted on a serviceable little horse, and rode with us for several miles. He was extremely polite, but seemed excessively stupid or ignorant, and at length dropped behind, as if he could not keep up. Perhaps he was a little afraid of us. He had a broad deer-skin belt at his waist, lined with cartridges, and supporting a horse-pistol, and, fastened to his sadddle, with the stock at his horse's tail and the muzzle at his head, was a very long musket, in a case of blue cotton stuif. The barrel lay under his knee as he rode. He was dressed in a blue jacket and black leather trovvsers, slashed d-own theleg; with a thick row of brass buttons, and open from the knee, so as to let the white underclothes flow loosely out. He wore on his head a tall, varnished, broad-brimmed, peaked black hat.

A journey through Texas; or, A saddle-trip on the south-western frontier

In paying my visits I was struck with the animation of Brownsville. I was made to understand that this was due to a number of Rancheros, or frontier farmers, who came in every day, either on horseback or in carts, to buy provisions and make other purchases for themselves, their families, and their friends. The streets were sadly cut up by the constant tread of horsemen, richly mounted indeed ; by the Arrieros, who loaded and unloaded their goods; by the Barilleros, called elsewhere aguaderos, or water-carriers. These poor fellows dress almost like the Lazzaroni of Naples. A shirt open in front and exposing the chest, with the sleeves tucked up to the shoulders, cotton drawers turned up above the knees, and sometimes a hat made of palm branches, make up the entire wardrobe of the Barilleros. It is they who furnish the inhabitants with water, bringing it from the Rio Grande in casks having two axles attached to their ends.

At home he is all filth, mounted on his horse he wears the gayest attire. Then he dons his broad- brimmed hat, lined with green and trimmed with an edging or chain of gold. He wears a clean embroidered shirt, and blue velvet trousers with broad facings of black, beneath which, through the extremities, may be seen his wide white drawers, while a blue scarf of china crape encircles his waist, and huge silver spurs clank at his heels.

Missionary adventures in Texas and Mexico. A personal narrative of six years' sojourn in those regions

but the ranchero never walks. Had he only half a mile to go, he does so on horseback. His horse, of which he is very proud, is his inseparable companion. He is content with a wretched hut for his residence, while he decorates his saddle and bridle with gold and silver ornaments. At home he is all filth, mounted on his horse he wears the gayest attire. Then he dons his broad-brimmed hat, lined with green and trimmed with an edging or chain of gold. He wears a clean embroidered shirt, and blue velvet trousers with broad facings of black, beneath which, through the extremities, may be seen his wide white drawers, while a blue scarf of china crape encircles his waist, and huge silver spurs clank at his heels.

Texas; with particular reference to German immigration and the physical appearance of the country; described through personal observation, by Dr. Ferdinand Roemer

Anglo osmosis 1820-1860

“… my neighbour Jameson Related to me a story Illustrative of the Good Faith of the southern Comanches, he says about the year 1823 on his way (In company with some friends) returning from a trading Excursion to Rio Grande their horses were stolen in the night time near the River Nueces in the morning the Party (considering themselves, Ruined if they did not Recover their prop-erty) mounted their few saddle horses which they had as usual kept tied near to the camp and pressed on the trail Entertaining a hope of Recovering their drove by the address of Jameson who had been an Old Comanchee trader; after some time in Persuit they came In sight. The drove was Halted and in an Instant the small Party or 4 in number) was surrounded and a demand made in spanish what do you want the Reply was that they were Americans and at peace with the comanches and had Persued to get their Horses. No Immediate satisfaction was given But Insisted on the Americans to Return and finally commanded them to Return to Camp and depend upon their Justice. Accordingly in 3 hours, all was Returned a Interview took Place and the Indians left. Two other cases are related by Mr Jameson of their having Fired on Americans in Mexican Dress and Wounding them Dangerously and on finding their mistake the Body was tenderly treated and Every Cumfort Provided

1837 May 9, W. CHRISTY] TO M. B. LAMAR

1 super blue Cloth Mexican Riding Jacket

1 Mexican riding Hat and Box.

[Transcript of invoice for Charles D. Sayre from John P.

Austin, October 22, 1831]:

Arthur left my plantation on the 12th instant, is about five feet ten or eleven inches high, about thirty-six years of age, straight in his walk; is a very black negro; his left ankle larger than the other, and occacionally walks a little lame; wore away a Mexican casinett roundabout, blue cottonade pantaloons and palmetto hat; took with him a black cloth coat and other clothing.

Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston, Tex.), Vol. 2, No. 37, Ed. 1, Saturday, September 23, 1837

General Houston had just returned from New Orleans, where he had been since the battle of San Jacinto for the purpose of having his wound treated. Being the President elect, he was of course the hero of the day, and his dress on this occasion was unique and somewhat striking. His ruffled shirt, scarlet eassimere waistcoat and suit of black silk velvet, corded with gold, was admirably adapted to set off his fine, tall figure; his boots, with short red tops, were laced and folded down in such a way as to reach but little above the ankles, and were finished at the heels with silver spurs. The spurs were, of course, quite a useless adornment, but they were in those days so commonly worn as to seem almost a part of the boots. The weakness of General Houston's ankle, resulting from the wound, was his reason for substituting bootsfor the slippers then universally worn by gentlemen for dancing.

Six decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock

Big Foot, yonder is a Mexican who has on a pair of pants large enough to fit yon." The Mexican in question was at this time assisting some of the wounded back to the rear. Wallace was a conspicuous figure during the fight. His dress, massive frame, and actions, while talking about the big Mexican, attracted the attention of General Caldwell, who rode up to him and said, "What command do you hold, sir ?" "None/' says Wallace. "I am one of Jack Hays' rangers, and want that fellow's breeches over yonder," at the same time pointing out his intended victim. Before the battle was over he killed him and secured the coveted prize, which was made of splendid material, and Wallace wore them the following year while a prisoner in Mexico after the unfortunate battle of Mier.

Early settlers and Indian fighters of southwest Texas

the story current at the time was that Gonzalvo's horse having been shot, a Mexican rushed upon him with a lance. Catching the lance, which was attached to the Mexican's wrist, he jerked his assailant to the ground, and himself mounting the Mexican's horse, dashed among the soldiers, yelling as loudly as any of them; and, having on a Spanish sombrero, he escaped detection amidst the confusion, and thus succeeded in getting through the Mexican line, and, once clear, having a good horse under him, he made good his escape.

Evolution of a state, or, Recollections of old Texas days

In addition to the German cloth cap, the covering for the head consisted of a broad-brimmed, peaked Mexican sombrero, or a fantastic fur-lined cap with the long tail of the native grey fox dangling from it.

Texas; with particular reference to German immigration and the physical appearance of the country

At one small table sat two men playing Eukre for the drinks. One, who was quietly playing his hand in a mild timid way utterly at variance with his hardened desperate appearance, was short and thick set, his face bronzed by exposure to the hue of an Indian, with eves deeply sunken and bloodshot, and coarse black hair hanging in snakelike locks down his back. His costume was that of a Mexican herdman, made of leather, with a Mexican blanket thrown over his shoulder.

My Confession

HORSE THIEF'S DRESS.

-The two men arrested some months since confessed to many things, among others a list of names of the gang and their dress by which each recognized the other where explanations were not convenient. The dress is an overshirt, the bosom of one color the body another, or the ruffle is one color the body another; pockets ornamented on each side of the breast. Pants made open at the side with rows of buttons; up the side, ribbon top and bottom; coats made josey fashion of any color, the ruffle is the mark; some times only down the front othere all around the tail In summer of calico, in winter of any heavy goods. The hunting shirt is the mark of some prominent We notice several just such dresses hereabouts, wonder if all who wear this dress belong to the gang -Crocket Printer

The Texas Republican (Marshall, Tex.), August 19, 1858

Comments