Shaving a Dead Horse

- David Sifuentes

- Jan 21

- 8 min read

The beard wars… if you want to see masculine emotions run high and harsh words traded in the world of early American reenacting communities just bring up facial hair. The levels of argument, counter argument, and justification that ensue are a sight to behold.

“Nobody cared on the frontier” “You can’t prove everyone did it”

Sometimes hard truths come out

“My wife would hate if I shaved”

If you’re lucky someone finds one quote about one guy somewhere and he clings to it like a barnacle. These debates rage in 18th century circles but does it have any effect on 19th century Colonial/early Republic Texas?

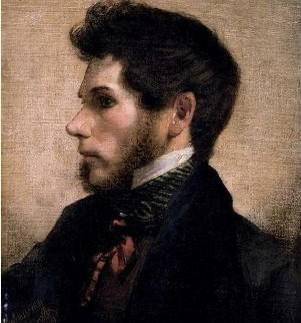

We’ll be sharing some of the only quotes I’ve found on the topic but first some context. The 1820’s and 30’s were still governed by the prevailing social norms of the enlightenment that facial hair was an excrement. If you were wearing any, you were for all intents and purposes, a poopoo face… unless you were on the cutting edge of fashion with side burns, which eventually for some adventurous soul became a well trimmed “uni-burn”.

If this is enough evidence for you that due to these men wearing beards the practice was mainstream let me remind you of the fashions we see trotted out from the “trendsetters” of today.

Nuff said.

This monstrosity of fashion was however being seen among the aristocracy of Europen powers and filtering its way into fashion plates and American circles even as far as the frontier.

Seen below is Prince Maximilian and Duke Frederich Paul Wilhelm traipsing across the West.

The trials and privations of the west as well led certain frontier Americans to indeed sport beards, although note, the ones depicted are far from the Duck Dynasty chia pets we see everywhere today.

The Rest is History podcast has a great program on beards and the attitudes towards them throughout Western history. It is a recommended listen for anyone on the fence about why beards matter in presenting a visual history.

Now, dealing specifically with Texas, let’s comb the sources and see if any common veins or reasons justify the hair these men were sporting:

Louisiana 1829

October 26, 1829

Pardon my scribbling, but this steamboat has a terrible thrust and shake. Now I know when I’ll write from Natchitoches, but I don’t know when will you receive my letter. At least, never worry. The same sun that lights you with its dawn sees me wander on the great rivers with my beard that has not been cut for eight days, my dagger and my wide shoulders, and then there is a God who is watching over me. May he also keep watch over those who are dear to me.”

East Texas 1830

In this region, no one knows exactly where, lives the famous assassin nicknamed

"the brigand of the Sabine." I’lI omit his name, even though it's rather poetic. No tangible proofs of his crimes exist, but he himself boasted, in front of a judge with whom he had to deal on a civil matter, about sinking his dagger into the heart of a man with the same amount of pleasure as into the steak of a deer. Today he's an old man, his hair all white, his long beard also whitened by the years, lends him an imposing air, respectable even, but this does not disguise the fire in his eye. Seven sons, vigorous young people, lead more or less the same life as their father— they terrorize the land.

Pavie in the borderlands : the journey of Théodore Pavie to Louisiana and Texas, 1829-1830, including portions of his Souvenirs atlantiques

Rio Grande Valley 1834

I was wearing neither a vest nor a jacket, and my trousers and boots were ripped and torn. I had a long stiff beard, long sideburns, and a large mustache, and I was burned as brown as a sweet chestnut. With a long, sour face, and carrying my little keg under my arm like a schoolbook, I bore no resemblance to the young stylish gentleman of the year before

letters by Eduard Ludecus, a German colonist, to friends in Germany in 1833-1834, recounting his journey, trials, and observations in early Texas

Lower Brazos River, 1835

April 12.--At the appointed hour we were all ready, with the exception of Mike Eastleman,”~ a celebrated woodsman and hunter, who was to act as our pilot. As none of our party had the slightest knowledge of the country, up the river, we were compelled to await the arrival of Mike. Towards twelve o'clock Mike's arrival was announced; his delay was caused by his not being able in time to find his horse. Mike was the first regular western hunter I had ever seen. He is about forty years of age, large in person, and vigorous in health and strength. He was dressed in leather, with the exception of a check gingham shirt, and a small ragged hat on the top of his husky head. His ample beard had not for the last two months felt the benefit of a razor, and from the soiled appearance of hands, neck and face, he was evidently terrestrial in his habits.

April 21

We stopped at twelve o'clock at a fine spring, and whilst our horses were grazing, some of us availed ourselves of this opportunity to shave. Mike sat on the hill, looking on. offered him the use of my razor, but, after feeling his beard

he replied, that it was not in order for shaving by three weeks. He however

stated, that if I would lend him my soap, he would wash his face and hands. This request

I complied with; and all agreed that Mike was, in appearance at least, much improved.

We encamp this night at a small creek, twenty miles from Viesco.

Papers concerning Robertson's Colony in Texas Volume X

Concepcion 1835

I had raised my own rifle to my shoulder, when I let it fall again in astonishment at an apparition that presented itself to my view. This was a tall, lean, wild figure, with a face overgrown by a long beard that hung down upon his breast, and dressed in a leather cap, jacket and moccasins.

Where this man had sprung from was a perfect riddle. He was unknown to any of us, although I had some vague recollection of having seen him before, but where or when, I could not call to mind. He had a long rifle in his hands, which he must have fired once already, for one of the artillerymen lay dead by the gun.

At the moment I first caught sight at

him he shot down another and then began reloading with a rapid desterity, that proved him to be well used to the thing. My men were as much astonished as I was by this strange apparition which appeared to have started out of the earth; and for a few seconds they forgot to fire, and stood gazing at the stranger.

The latter did not seem to approve

of their inaction.

'Ye starin' fools,' shouted he in a rough hoarse voice, 'don't you see them art'lery-men? Why don't ye knock 'em on the head?'

Vermont phœnix (Brattleboro, Vt.), March 19, 1846

Nacogdoches 1836

The plan would have had the most beneficial effect on the discipline of the rest of the corps which in their unruly and undisciplined state can be likened more to a band of robbers than to a military organization. The individual members know nothing of obedience; the danger they face in common can bring the only unifying force. No thought was given to having a uniform or even to a similarity in clothing. A few individuals had made coats for themselves out of various colored patches of cloth; but, in general, about all they had in common are ragged clothes and unkempt beards.

A choice example of originality in dress was a captain. His long hair and longer beard reminded one of the late German demagogues; a red flannel Phrygian cap? called to mind the French Jacobins. An added feature to the cap for protection were visors made of alligator hide attached to the front and rear of the cap. Where his personal needs were concerned, he knew about the time and place to obtain these. His clothing, decorated with faded colored ribbons, was a tattered old uniform which he personally made from tent scraps; and his shoes, made of pelt, reminded one of the Indian moccasins. He was quite vain about his attire, and often I saw him admiring himself in front of an old broken mirror

Sketches of life in the United States of North America and Texas

San Jacinto 1836

Immediately on my landing, I repaired to the General's tent, aud deliver ing my despatches, looked around me to observe our position.

A scene singularly wild and picturesque presented itself to my view. Around some twenty or thirty camp-fires stood as many groups of men, English, Irish, Scotch,

French, Germans, Italians, Poles, Yankees, Mexicans, &c., all unwashed, unshaven, for months, their long hair, beard aud mustachios, ragged and matted, their clothes in tatters, and plastered with mud; in a word, a more savage band could scarcely have been assembled, aud yet many, indeed, were gentlemen, owners of large estates, distinguished some for oratory, some for science, and some for medical talent, many would have, and had graced the drawing-room.

The North-Carolinian (Fayetteville [N.C.]), September 7, 1844

Washington on the Brazos 1837/8

I recollect well Moses Evans (alias "The Wild Man of the Woods"). This man was at one time famous all over Texas and a great many of the states. He was tall and raw-boned, had light hair, almost red, and wore a long, fiery red beard, which he divided and plaited, and usually tied the ends with narrow red or blue ribbon. He was very eccentric and in some respects was a marvelous man.

At first he only thought it a pleasant glow from the excitement under which he was laboring, but presently the oil commenced to follow down the great streams of perspiration and found lodgment in his immense red beard

Sixty years on the Brazos; the life and letters of Dr. John Washington Lockhart, 1824-1900

Galveston 1839

The other day I was seated on a cotton bail & musing upon the rise & fall of Stocks & kingdoms, when the impersonation of Jeremy Diddler accosted me. He was admirably dressed for the part, having on his back, an old thread bare black coat buttoned very tight up to the throat where it was met by Brownish black silk handkerchief disposed in so careful a way, as to suggest to the thinking mind, that the washerwoman had not yet sent home the gentleman's clean linen. His nether person was clothed in sombre unwhisperables with a mellowed autumnal tint upon them, these reached half way down a pair of Boots the footing of wh having been neglected, & permitt casual glimpses of flesh, announced the absence of stockings. On the head a covering was lightly thrown having the appearance of a "Soufflet" after the first dig of a spoon, being of a Brownish hue, sunk in at the top, & turned up all round. In keeping with his attire was his face which was excessively dirty, the chin being adorned with a stubby black beard of about 3 weeks old.

Journal of Francis C. Sheridan 1839

Did you pick up the general reasons given for each? Beards from circumstance, heavy doses of eccentricity, tied to poverty, or… tied to being German. Nuance and logic should dictate whether those scenarios may be part of your living history persona. Till next time!

Comments